Lake sturgeon nearly disappeared from the Great Lakes 100 years ago. Discovering the secrets of their biology to help recover the species is a group effort. Today, Catherine Gatenby takes us on a journey to the Niagara River, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario with fish biologists who are diving deep into sturgeon waters to find answers we need for helping this ancient species of fish.

While the quest for lost treasure chests of information about lake sturgeon might not be considered fodder for an Indiana Jones movie, the discoveries may be more valuable than gold to fish biologists. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office and Northeast Fishery Center along with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the U. S. Geological Services and Shedd Aquarium are working together to recover lake sturgeon.

Their pursuit to uncover the secrets of this ancient fish doesn’t include excursions into dark caverns or midnight camel rides across the desert. However, it does involve dives into the blue waters of the Niagara River and breathtaking adventures on the expansive Great Lakes. It takes a dedicated team of scientists, engineers, boat captains and barge operators to restore lake sturgeon and its habitat.

Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office and Northeast Fishery Center lake sturgeon restoration crew out on Lake Ontario. Photo credit: USFWS

Far less is known about the lake sturgeon in lakes Erie and Ontario than in the other Great Lakes. Questions we ask ourselves as we embark on this adventure include: How many sturgeon live here? Where do lake sturgeon spend their lives? Where is the best habitat for spawning and feeding? What do they eat? How many adults are reproducing? And the ultimate question we aim to answer is: How long before we can consider the population healthy and self-sustaining in the Great Lakes?

“We collect valuable information by tagging wild fish. We learn about their movement, diets, hormone levels and genetic diversity to help us answer these questions,” says Dr. Dimitry Gorsky, of the Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office.

Fish biologists with the Northeast Fishery Center and the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, Illinois, implant a tag that will transmit valuable information on migratory behaviors of lake sturgeon. Photo credit: Shedd Aquarium

Biologists are observing an increase in lake sturgeon numbers in many remnant populations across the Great Lakes. “Over the past four years, we have captured and uniquely marked over 600 individual fish. We used to catch between 15 to 20 fish per year just 10 years ago,” reports Dr. Gorsky, “but we are steadily capturing more lake sturgeon, more than 100 fish each year. This summer, we have already captured nearly 200 fish and are on our way to a record year.”

Northeast Fishery Center biologist releases a wild lake sturgeon after collecting vital information that will help evaluate overall health of the population. Photo credit: USFWS

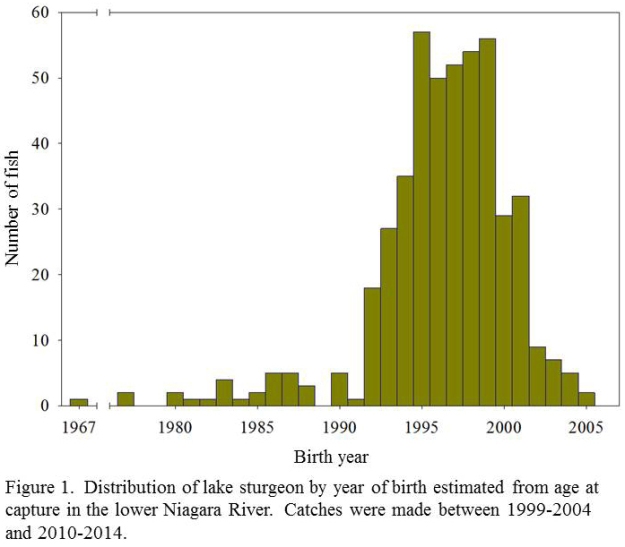

The age distribution of lake sturgeon are eerily similar among different populations as those observed in the lower Great Lakes; most are less than 25 years old, suggesting that this ongoing recovery is in response to large-scale actions that took place many years ago. The first of which may be the Clean Water Act of 1972, which set the table for preventing and removing pollution from our waters. Also in the 1970s, some U.S. states along with the Province of Ontario, Canada, enacted fishing closures on lake sturgeon to protect what fish were remaining, according to Gorsky.

“For species that delay reproduction, such as the the lake sturgeon which doesn’t reproduce until at least 10 to 15 years of age, it would naturally take decades to see an increase in population growth, assuming the causes for the decline have been abated,” says Dr. John Sweka of the Northeast Fishery Center.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service fisheries biologists study the gentle and ancient lake sturgeon to help with its recovery. Photo credit: USFWS

The combination of setting harvest limits and improvements in water and habitat quality is creating a favorable environment for lake sturgeon recovery. “It’s amazing that actions begun so long ago continue to be linked to improvements in our Great Lakes,” remarked Dr. Gorsky. “Perhaps the greatest secret lake sturgeon may have revealed to us is that recovery takes time.”

Read more about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s high-tech tracking of lake sturgeon in the Buffalo Harbor, NY.

Read more about the Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office and the Northeast Fishery Center