It’s National Invasive Species Awareness Week, a time to call attention to and identify solutions for combating the adverse impacts of invasive species on the ecological and economic health of our natural resources. Heidi Himes, along with other biologists at the Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office are diligently working to detect and prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species in the Lake Erie and Lake Ontario drainage basins, and the Erie Canal. Today Heidi shares some insight into their invasive journey.

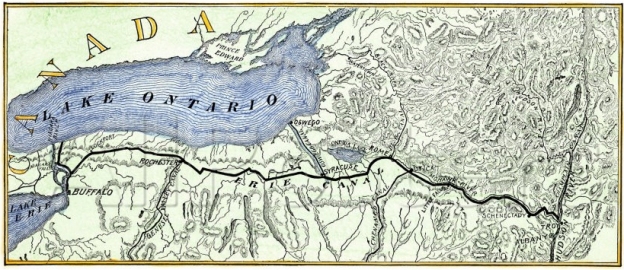

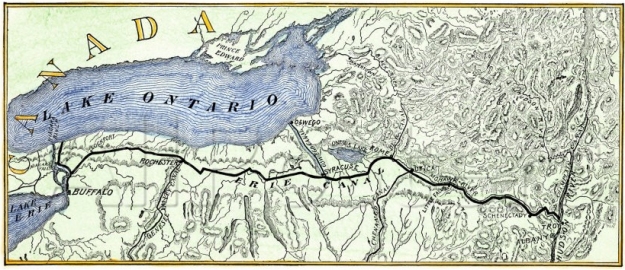

Many of the canal systems of the world were designed to increase the flow of goods across countries and continents, thereby fueling national and global economies. The Panama Canal, the Suez Canal and the Erie Canal are some of the most well known.

Not only do these canal systems increase the flow of goods, they also contribute to the flow of species across watersheds and across the globe to the detriment of many native species. So in essence, canals can act as super-highways for invasive species, granting access to areas that otherwise would have been inaccessible or impassable due to natural geographic barriers.

For example, the most recent glacial retreat 12,000 years ago left Lake Ontario separated from Lake Erie by a not too small barrier called Niagara Falls. Then, in the 1800’s and early 1900’s, construction of the Chambly and Champlain Canals in Vermont, the Erie Canal in New York and the Welland Canal in Canada bypassed the natural barriers glaciation had created – allowing species such as the sea lamprey to migrate into Lake Ontario and westward all the way to Lake Superior. The introduction of sea lamprey into new waters contributed to the decimation of native lake trout in the Great Lakes.

Biologists from the Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office monitor fish species in the Erie Canal. Photo credit: USFWS

The invasive round goby also has caused impacts upon the economy and ecology of the Great Lakes since it’s arrival in the 1990s. In addition to eating lake trout eggs, they out-compete native fish species like darters and sculpins, which are essential food items for larger sport fish. The round goby is now spreading eastward to the Finger Lakes and the Hudson River through the Erie Canal.

Fish biologist Kelly McDonald, delineates the extent of the hydrilla infestation. Photo credit: USFWS

Non-native aquatic plants such as hydrilla, water hyacinth and water chestnut also have the potential to spread across New York through the Erie Canal. These aquatic plants crowd out native plants, damaging habitat for fish, amphibians and birds.

Luckily, wildlife and fisheries biologists have learned that with early detection they are better able to eliminate and control the spread of these harmful species.

A team of biologists from the Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office in Basom, New York are hard at work monitoring invasive fish and plant species at several connection points along the Erie Canal. Two such locations are the intersection of the canal and the Genesee River in Rochester and the Seneca-Cayuga Canal which links the Erie Canal to the beautiful Finger Lakes region.

“Early detection at these critical junctions can help us respond rapidly to prevent invasive species from spreading to a new water body, “ says Sandra Keppner, the Northeast Regional Aquatic Invasive Species Coordinator. “While we observed the round goby near Utica, New York – over half way from Lake Erie to the Hudson River, the good news is that we haven’t seen any new invasive species.”

Biologists are also helping control hydrilla, one of the most rapidly spreading invasive plants threatening recreational fishing and boating. Hydrilla chokes valuable fish habitat, which can reduce oxygen levels and cause fish kills.

They first found hydrilla at the western end of the Erie Canal in 2012. Heavy recreational traffic cuts the plants into fragments, like cuttings for new houseplants, which flow along the canal and establish more colonies. After biologists found hydrilla a few miles further east in the canal in 2013, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers led a collaborative effort with the New York State Canal Corporation, the Lower Great Lakes FWCO and the New York Department of Environmental Conservation to remove hydrilla in the 15-mile section from the Niagara River east to Lockport, New York. “We are pleased to report that treatments applied in 2014 and 2015 greatly reduced the mass of hydrilla in this area” says Sandra.

After one season of using a mechanical harvester to remove water chestnut, we can see the surface of the Erie Canal again and pathways created by fish moving through the matted canal. Photo credit: USFWS

Another successful effort in our battle against invasives is the control of water chestnut in the western end of the Erie Canal before it enters the upper Niagara River. “Back in 2010, we were mechanically removing this plant by the cubic yard, with amounts weighing 100,000 lbs. Local residents would say they saw ‘squirrels running on the water’, when the water chestnut was so dense. Today, we are removing 200-400 plants in an entire summer, using just our hands which allows us to remove the root along with floating leaves,” says Mike Goehle, Deputy Manager, Lower Great Lakes FWCO.

After two seasons of mechanical removal, the western end of the Erie Canal is nearly free of water chestnut. Photo credit: USFWS

Aquatic species invasions are no joke, they can be vectors of viruses and disease to which native species have no resistance, they can decimate native species and destroy habitat. Canals systems are likely here to stay, and will continue to act as super-highways for aquatic species. Outreach and education to raise awareness of the problems and how to prevent the spread of invasive speciescan help make the positive changes needed to protect aquatic landscapes.