If you’re an avid birdwatcher, nature lover, or even just enjoy going for a stroll near your home, you’d probably be thrilled to see a yellow warbler whizz by or hear its cheerful “sweet- sweet- sugary- sweet” song ring through the trees.

Yellow warbler, photo by Tom Teztner

While many of us enjoy wildlife encounters like these, the experience isn’t the same for everyone.

Generally, avid birders and ornithologists rely on calls and songs to identify nearby birds just as much as they use their sight. But for birders who are deaf or hard of hearing, birding by sound can prove a difficult, or even impossible, task. In an effort to overcome this challenge, Ron Popowski – who is deaf – and former U.S. Forest Service colleague in northern Arizona, Hans – who is hearing- have developed a helpful life hack to help deaf birders better locate birds for identification.

With a series of hand signals and motions, Hans tips Ron off to a bird when it vocalizes. With his knowledge of ecosystems and bird behavior, Ron is able to deduce the general habitat and locate a bird for a species-specific identification. This way, Ron can still enjoy the same challenge that comes with identifying birds without simply being told what it is.

For example, Hans may hear a “tap tap tap tap” in the woods and therefore signal “woodpecker” for Ron. Ron can then determine the general habitat, height, and possible direction to visually locate the woodpecker. From there, he can determine it is a yellow-bellied sapsucker.

The spelling and ASL sign for ‘woodpecker’ video by ASL Stem Forum

This silent code proved beneficial for data collection when Ron and Hans created it in the 1990s. The pair were working on several analysis areas in Coconino National Forest to collect baseline data, and their code allowed Ron to expand his data collection to record bird species. They worked in diverse habitats, including treeline and tundra, ponderosa pine and spruce-fir forests, pinyon-juniper, chaparral, grasslands, desert scrub, riparian, and marsh and open water. Some of the species included Clark’s nutcracker, doves, poorwill, warblers, wrens, sandhill crane, Northern goshawk, and Mexican spotted owl.

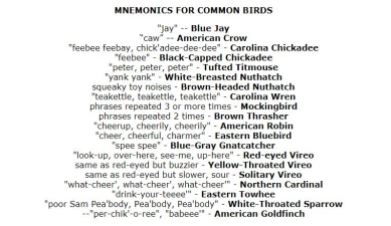

It’s helpful to remember that everyone’s needs are different. Some alternatives to Ron’s Manual may be more beneficial for birders with limited hearing. For example, bird songs are often given phonetic spellings or mnemonics, to assist hearing or hard of hearing birders alike to remember and identify songbirds. To some the red-eyed vireo may sound like it’s saying “look up, over here, see me, up here.” Giving words to notes could help some to better distinguish sounds.

Additional tools are available for those with high-register hearing loss, or presbycusis. While costly, devices like SongFinder are available to lower the pitch of bird calls without slowing them down, allowing a birder to detect its pattern and rhythm in a lower, audible register.

We are always looking for more tips and tricks that can be useful for recreationists to enjoy the outdoors. If you have helpful tools or strategies that improve your experiences in nature, we’d love to learn from you. Please comment and share!

Ron Popowski is Endangered Species and Conservation Planning Assistance Supervisor at the New Jersey Field Office.